In Drury University’s oldest stone building, the 1906 Chalfant Pipe Organ can be heard. The Stone Chapel stained glass casts a pastel glow about the sanctuary, illuminating the dust throughout the room, which lands softly on the pews. Dr. Earline Moulder sits on the organ’s stool, her hands and feet methodically pumping rhythm through the pipes.

Moulder’s done this for years. She started learning how to play on the Stone Chapel organ when she was 9. Now, decades later, she serves as Drury’s university organist, a role she’s filled since 1991. Moulder said organs are still valuable to our society, and should be appreciated, just as the Chalfant Organ is.

“People are saying, ‘Organists are just a dead group now … and no new organs are being built,’” Moulder said. “But they’re being built everyday — wonderful organs.”

After graduating from Drury with undergraduate degrees in music, biology and French, she earned her master’s degree at Indiana University and eventually received her doctorate from the University of Kansas.

Earline said she knew she wanted to dedicate her life to playing the organ after an experience when she was young.

“It’s kind of hard to talk about,” Moulder said. “When I started playing the organ and taking lessons here, one Saturday afternoon I was practicing. My father had (snuck) into the church to hear me, and was … in a dark corner. I looked back, and a tear was coming (down his face.) From that tear, I said, ‘I have to do this this forever.’ And I love the organ, it’s the most wonderful thing in the world.”

She said her parents were asked at her childhood church in Buffalo, Missouri, if she would play the organ for services. But her parents would not allow it without formal training.

Moulder speaks fondly of her first organ instructor, Thomas Stanley Skinner, dean of the Drury Conservatory of Music from 1920-1950. Skinner took on Moulder as an exception, as he had never taught anyone under college level before, Moulder said.

She returned to teach piano and organ at Drury after graduate school, before filling her formal role as university organist. Through those years to now, she has taught piano and organ to Drury students, updating the organ along the way with her husband David Plank, who is an engineer.

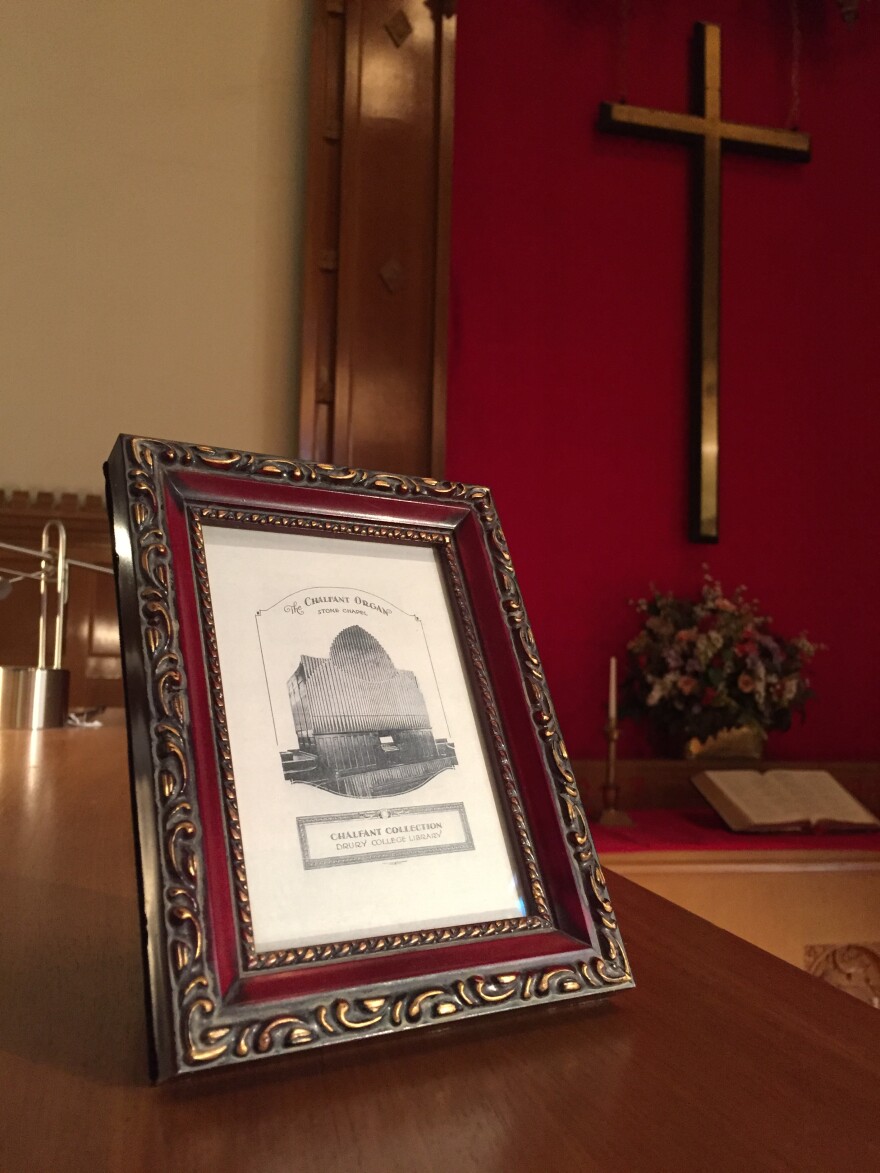

Moulder said their work adding stops and ranks to the organ have only added to its versatility, and allowed for the playing of various styles of organ music from medieval times to hits you can hear on the radio today. Stops are handles that send air to a set of similar pipes, which can provide a certain sound. The organ is a three manual, 30-rank instrument with approximately 1,400 pipes, according to Drury’s website.

Playing the organ has taken Moulder all over the world. She has performed in Australia, Chile, England, Germany, Austria, several churches in France, Poland and Slovakia, among many other venues. And she and Plank own an apartment in Paris, one block from the church of Saint-Sulpice, and live there part-time.

“It’s taken us to places we would probably never go,” Moulder said. “And we’ve learned so much you can’t learn in a textbook. It’s just a wonderful opportunity.”

Bill Garvin is the director of Drury’s F.W. Olin Library and the university archivist. Garvin gave insight into the history of the 1906 organ, and the chapel’s long history.

The last step in completing the chapel, he said, was to install a furnace in December 1882. But the instructions for installation were very specific.

“And unfortunately the local contractor who installed the furnace did not follow those instructions and when the furnace was fired up it burned the chapel completely to the ground,” Garvin said.

Stone Chapel took another ten years to rebuild, and building an organ in the chapel wasn’t thought of until a few years later.

Garvin said many might assume the organ was financed by William Chalfant because it’s named after him. Chalfant was the dean of the Drury conservatory of music at the turn of the 20th century. But the organ was actually paid for by private donors because of the work done by Chalfant’s wife.

“I think people just assume that (the organ) is named after William Addison Chalfant, and it is. … But the person who was really the driving force behind the organ was Hattie Leach-Chalfant, dean Chalfant’s wife,” Garvin said.

Leach spent three years fundraising to purchase the organ. And on Jan. 31, 1906, Lyon and Healy of Chicago put forth a contract for the organ’s construction. The contract was signed by a representative from the company and Hattie Leach-Chalfant, former Drury president J. Edward Kirbye and William Chalfant.

Garvin said President Kirbye stayed with Drury for only two years, and Garvin noted one of the reasons given for his dismissal found in Drury’s special collections.

“(Kirbye) had not consulted with the board of trustees before the purchase of the organ,” Garvin said. “It was something of a little scandal on campus that the president had not consulted with the board of trustees.”

Daniel Hancock graduated from Drury in the spring of 2004 with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the Drury Hammons School of Architecture. While there, he trained with Moulder on the Chalfant Organ.

Hancock is now the president for Quimby Pipe Organs, an organ-building company based in Warrensburg, Missouri. Hancock grew up in Mountain Grove, Missouri and said, though there was small pipe organ there, he had no one to formally teach him. His organ instruction didn’t happen until he went to college.

Hancock was at Drury his senior year of high school and happened to see Moulder’s name on the wall outside her office. He jumped at the chance to speak with the university organist — he said he knocked on the door.

“And announced to her that I was coming to Drury the next year and was going to be taking organ lessons, and she just looked at me like, “Oh, you are?” Hancock said. “It never occurred to me that I would have to ask if she wanted to teach (and) as it was, she was happy to do it.”

Hancock said he now oversees building organs “five times bigger” than the one in Stone Chapel, as well as smaller projects across the country. For example, in 2015, Quimby Pipe Organs completed construction on an Opus 71 — a 5-manual, 142-rank pipe organ in Chicago’s Fourth Presbyterian Church. The new construction made use of the former 1914 Skinner and 1971 Aeolian-Skinner organs, according to Quimby Pipe Organ’s website.

After Hancock’s experience training with Moulder and up to his knowledge now of pipe building and tonal variations, he recognizes the uniqueness of the Chalfant Organ.

“That organ has a very romantic voice that — being a turn of the 20th century instrument — has very colorful stops that blend together and very, in some ways, warm ensembles,” Hancock said.

Hancock said, though Moulder was working with students from different levels of organ knowledge, she treated all students the same — sharing her expertise in the craft. Hancock said Moulder taught him there was more to music than getting good enough to be paid for it.

“And I think because of that reason I never thought of myself as any less of an organist than someone who was doing it full time,” Hancock said. “That is one reason out of many that I will remain grateful to her always.”

On a recent weekday, Moulder’s husband David sat near the organ on an aged, brown pew and softly closed his eyes, listening to Earline play, as she has for many years. Peace overtakes the chapel; all that can be heard are the pipes.

Moulder believes the organ, and music altogether, has an important role in today’s society. She said some have questioned the relevance of the organ outside of the church, and she is quick to say that the power of music, including organ music, will never fade.